Tikopia: A Remote Pacific Island Preserving Ancient Traditions

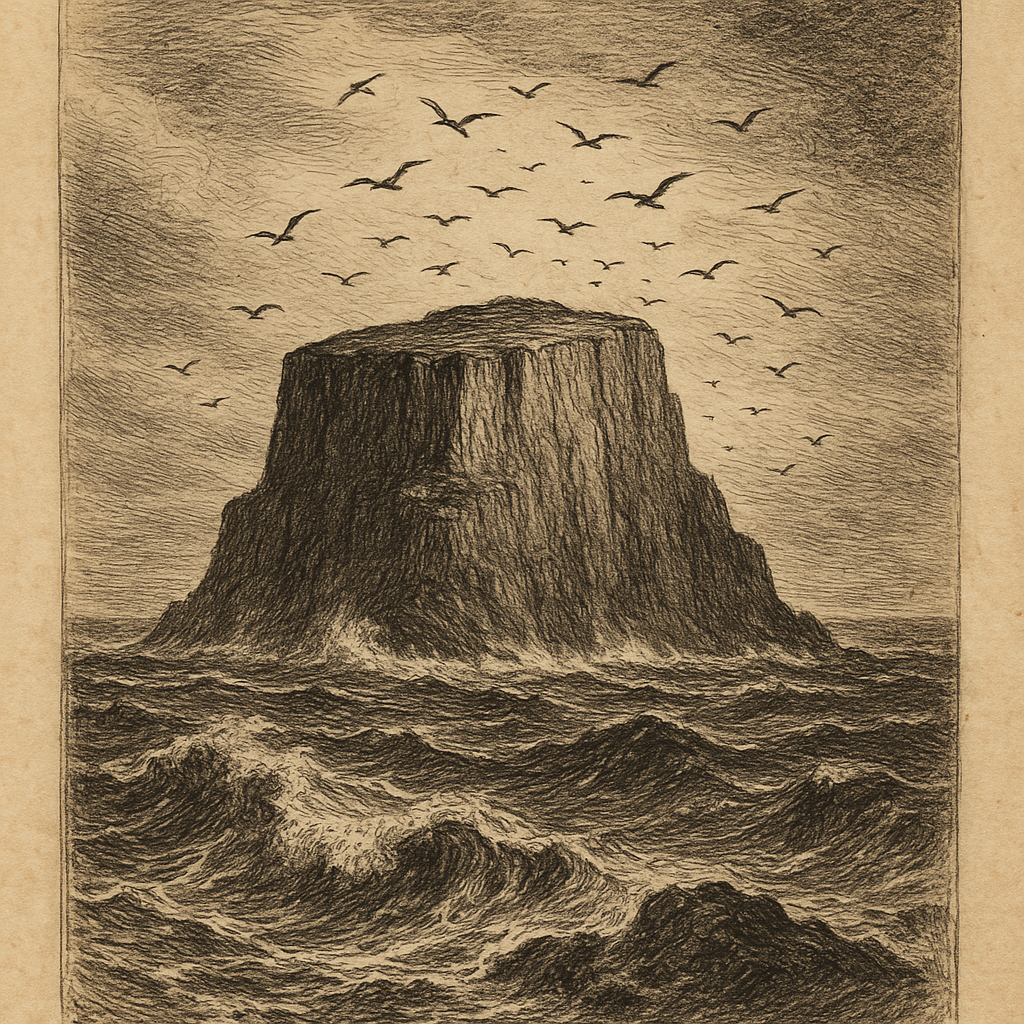

Tikopia is a small, volcanic island located in the southeastern Solomon Islands, part of the Temotu Province in the South Pacific Ocean. Despite its small size—only about 5 square kilometers—it is known for its rich cultural heritage, self-sufficient lifestyle, and remoteness. The island has captivated anthropologists, travelers, and environmentalists for decades, given its unique blend of isolation, sustainability, and tradition.

Location and Geography

Tikopia lies approximately 1,200 kilometers east of the main Solomon Islands chain, nestled within the Pacific Ocean’s vast blue expanse. It is part of the Santa Cruz Islands and represents one of the most remote inhabited islands in the region. Tikopia is a high volcanic island rather than a low-lying atoll, giving it a rugged terrain with a central volcanic peak known as Mount Reani. The island’s crescent-shaped perimeter encloses the crater lake Te Roto, a dominant inland feature formed from the remains of the once-active volcano.

With its tropical climate, Tikopia experiences heavy rainfall throughout the year, supporting lush vegetation. However, the island is vulnerable to cyclones, which have periodically caused significant destruction.

Volcanic Origin and Environment

Tikopia’s geological origin is largely volcanic, formed by the uplift and activity of tectonic plates in the Pacific Ring of Fire. Over millennia, the island’s volcanic activity ceased, leaving behind fertile soils and a dramatic landscape of cliffs, beaches, and forests. Unlike coral atolls covered only lightly with soil and vegetation, Tikopia’s volcanic base allows for more diverse agriculture and supports a broader ecosystem.

The surrounding lagoon and coral reefs host a variety of marine biodiversity, including colorful reef fish, sea turtles, and occasional sightings of dolphins and whales. Inland, despite its small size, Tikopia maintains surprisingly rich flora and fauna, though many species were introduced through centuries of human habitation.

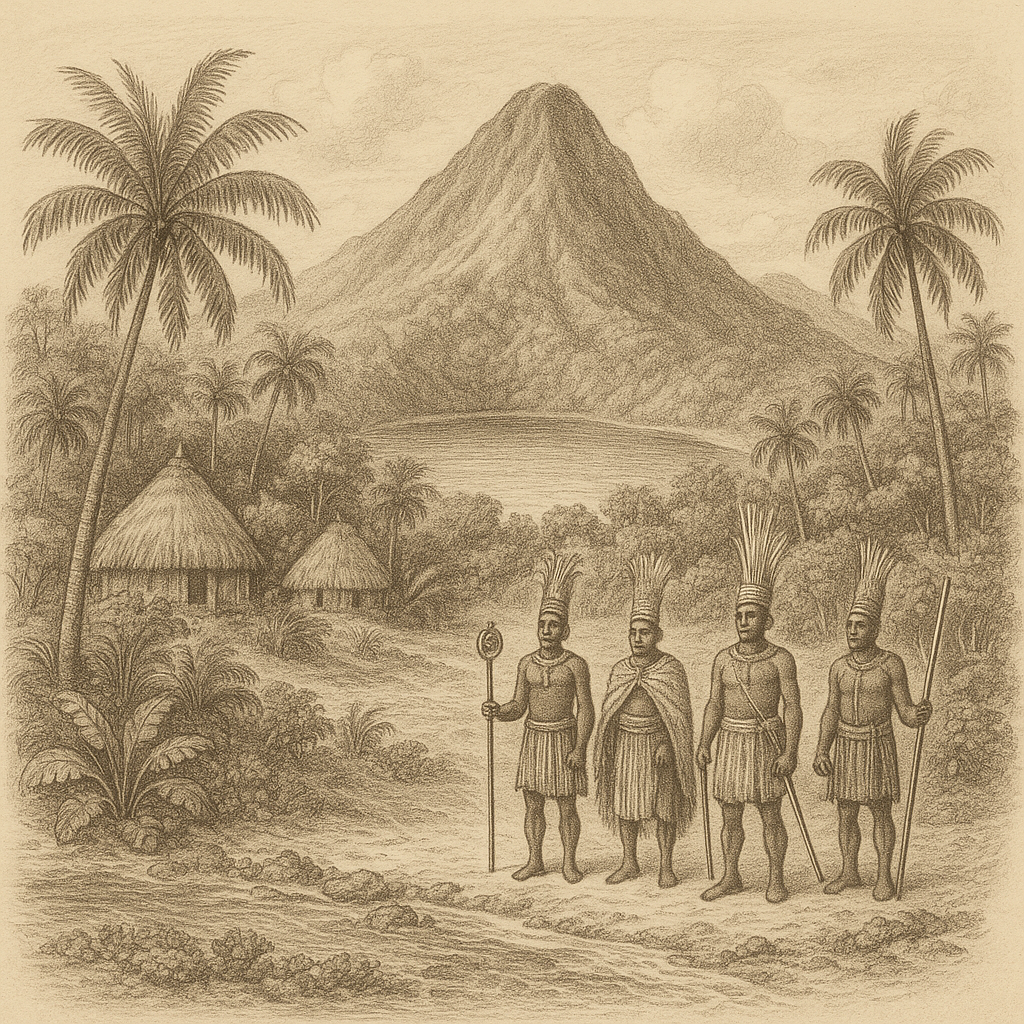

Culture and Traditional Governance

One of the world’s most studied examples of sustainability and social organization, Tikopia is unique in its cultural and societal structures. The population, historically around 1,200 people, descend from Polynesian settlers rather than the Melanesian populations that dominate the Solomon Islands. As such, Tikopians share linguistic and cultural traits with other Polynesian outliers like Anuta and Rennell.

Tikopia’s society is governed traditionally by four chiefs, each representing a clan. The chiefly system plays a central role in social cohesion, decision-making, and resource management. Land is communally managed, and the chiefs oversee everything from agriculture cycles to community disputes. The societal structure emphasizes collective well-being over individual accumulation, contributing to its ecological sustainability.

A Model of Sustainability

What has drawn global attention to Tikopia is its centuries-old model of sustainable living. Facing limited land and resources, Tikopians engaged in long-term strategies to ensure survival. Practices such as shifting agriculture were abandoned in favor of permanent gardens. Pigs, once a major food source, were eliminated around the 17th century because their environmental impact outweighed the benefits. Instead, fish and plant-based diets became the norm.

Population control was also actively managed through cultural norms. This included celibacy before marriage, infanticide in extreme cases, and emigration, ensuring the population remained within the island’s carrying capacity. Anthropologist Raymond Firth and later Patrick Kirch highlighted Tikopia as a functioning example of long-term ecological balance in small-scale society.

Interesting Facts

Tikopia may be small in size, but it boasts an array of fascinating features:

– Tikopia remained entirely pagan and polytheistic until as late as the 1950s, after which Christianity was introduced. However, many old customs are still practiced alongside religious teachings.

– The island has no modern facilities such as cars, hotels, or supermarkets. Most houses are made of traditional materials like pandanus leaves and bamboo.

– Despite the isolation, Tikopians maintain strong oral history traditions, passing down genealogies and legends with remarkable accuracy over generations.

– Communication with the outside world is limited but has improved in recent years with intermittent radio and satellite connections.

– The community survives almost entirely on subsistence farming and fishing. Common crops include taro, yam, and coconuts.

Legends of Tikopia

Tikopia is steeped in oral traditions and legends that form an integral part of the island’s identity. Among the most famous tales is that of the ancestral canoe voyages that brought the first settlers from the east—possibly from Samoa or Tonga. These early voyagers were said to be guided by stars and ancestral spirits, establishing the four clans that remain to this day.

One enduring legend involves the spirit of Mount Reani, the island’s central volcano. It is said that Reani is watched over by a powerful mountain god who protects the islanders but punishes greed and selfish behavior. Violent storms are often interpreted as spiritual warnings, and signs of volcanic tremors are carefully watched as messages from the gods.

Other myths recount the story of great fish that control access to the reef, teaching fishermen to respect the marine environment. These stories continue to guide community behavior, tying spirituality directly to environmental stewardship.

Modern Challenges and Preservation

Although Tikopia has maintained traditional practices for centuries, modernization is slowly encroaching. Climate change poses a new and significant threat, with rising sea levels and stronger storms undermining the island’s coastal defenses. Cyclone Zoe in 2002 devastated much of the island, though the community’s quick reorganization highlighted their resilience.

Efforts are being made to document and preserve Tikopia’s intangible cultural heritage while supporting sustainable development. NGOs and anthropologists work alongside local leaders to ensure that modernization does not erode the community’s core values and environment.

Conclusion

Tikopia stands as a remarkable example of harmony between human society and nature. Isolated in the South Pacific, it has cultivated systems of governance, agriculture, and population management that have allowed it to thrive for centuries. As environmental challenges mount globally, Tikopia offers timeless lessons in sustainability, resilience, and community — a living proof that ancient wisdom can guide modern survival.