Kure Atoll: The Remote Northwestern Frontier of Hawaii

Kure Atoll, also known by its Hawaiian name Hōlanikū, is one of the most remote and ecologically important coral atolls in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Displaying a unique blend of isolation, natural beauty, and cultural significance, Kure Atoll represents a fascinating chapter in the story of the Pacific Ocean’s most distant islands.

Geographical Location and Geology

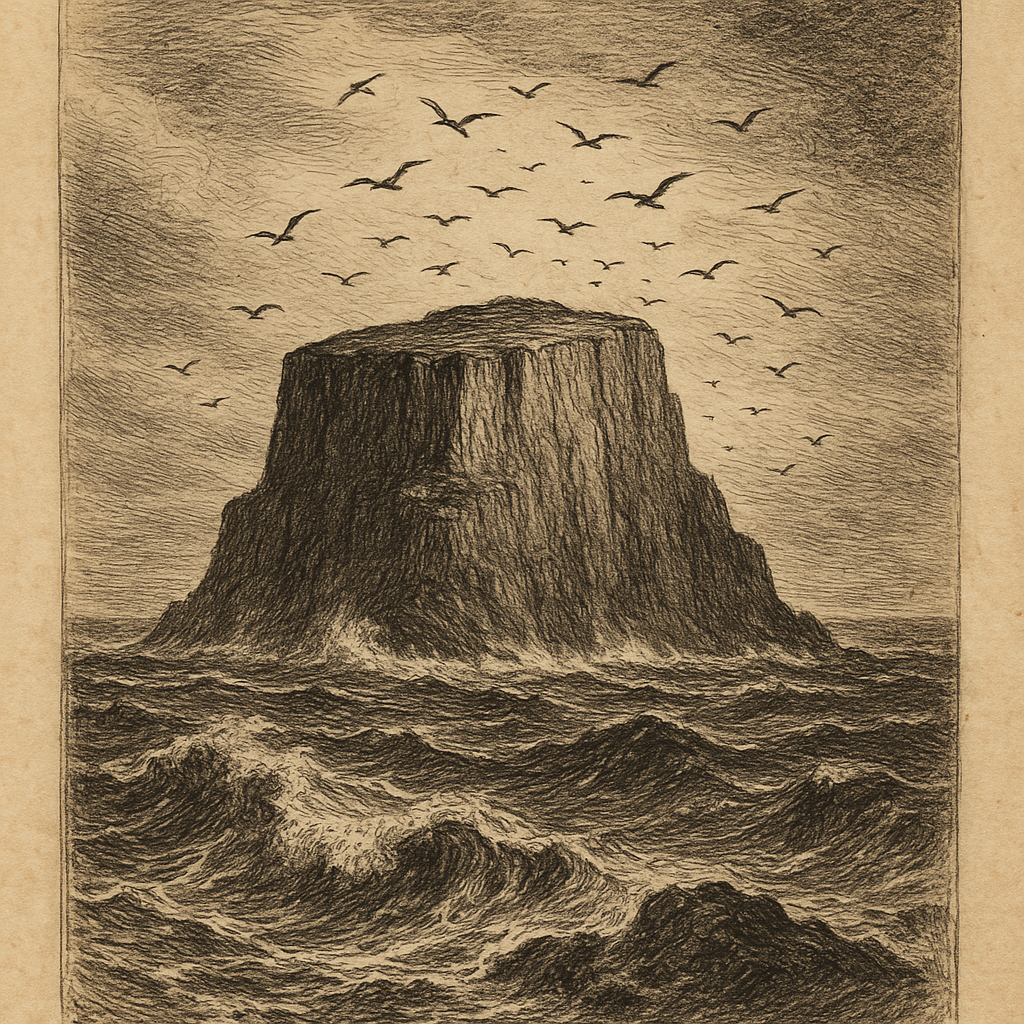

Kure Atoll is the northernmost atoll in the world, located approximately 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) northwest of Honolulu, Hawaii, and just 90 kilometers (56 miles) northwest of Midway Atoll. It sits at the western extreme of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and marks the end of the volcanic island chain that forms the Hawaiian Archipelago. Due to its position at the edge of the Emperor Seamounts and Northwestern Hawaiian seamount chain, Kure Atoll is often exposed to intense oceanic conditions, including heavy surf and strong currents.

The atoll spans approximately 10 kilometers in diameter and encloses a shallow lagoon. Like many atolls in the Pacific, Kure is the result of a long geological evolution: it began as a volcanic island millions of years ago and gradually sank due to crustal subsidence while coral growth kept pace at the surface, forming the present-day atoll. Unlike many tropical atolls located on continental shelves, Kure Atoll rises steeply from the ocean floor, giving it a distinct profile in bathymetric charts.

Ecology and Biodiversity

Kure Atoll is rich in biodiversity, hosting a variety of marine, bird, and plant life. It lies within the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world. The atoll’s isolated location has allowed numerous species to evolve with little human interference.

The coral reefs that surround Kure Atoll form vital habitats for over 30 species of coral and more than 300 species of fish. Notably, the reefs support populations of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi), and a wide range of invertebrates. The atoll’s small landmass, Green Island, serves as a nesting ground for seabirds like the Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis), black-footed albatross, red-footed boobies, and white terns.

Introduced species such as rats and invasive weeds once posed serious threats to the island’s ecology. However, extensive conservation efforts have restored natural balances, allowing native species to reclaim their habitats. Today, monitoring and habitat restoration activities continue under the guidance of the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources and the nonprofit organization Kure Atoll Conservancy.

Climate and Environmental Conditions

The climate of Kure Atoll is classified as tropical marine, with moderate year-round temperatures, high humidity, and steady trade winds. Rainfall is relatively moderate, with most precipitation falling during the winter months. Its remote location makes Kure susceptible to storms and rising sea levels, both of which are increasing concerns due to climate change.

Freshwater resources on Green Island are extremely limited, consisting mainly of rain collected in shallow depressions. As a result, any long-term human presence depends entirely on rainwater collection and storage systems.

Human History and Occupation

Kure Atoll has a storied history of exploration, shipwrecks, and conservation. Its first recorded sighting by Western explorers was in 1820 by the Russian expedition under Captain Staniukovich. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the atoll was notorious for shipwrecks, including the Norwegian ship Austrian in 1873 and the Japanese ship Amakasu Maru in 1942—the latest during World War II.

In the 1960s, the U.S. Coast Guard operated a LORAN (Long Range Navigation) station on Green Island until early 1990s. Since then, the atoll has not had any permanent human residents. Today, it remains uninhabited except for small seasonal conservation teams who stay on the island temporarily to conduct research and monitoring.

Legends and Cultural Significance

In traditional Hawaiian navigation and oral history, Kure Atoll—known as Hōlanikū, meaning “heavenly pathway”—holds significant spiritual and navigational importance. Ancient Hawaiian voyagers likely used it as a marker on their exploratory journeys through the Pacific, though permanent settlement was unlikely due to its remoteness and lack of fresh water.

According to legend, the souls of the deceased would travel northward from the main Hawaiian Islands toward Hōlanikū on their way to the afterlife. It symbolized the final frontier of existence—a place between the physical and the spiritual realm. Though rarely included in historical Hawaiian place names, Kure’s role as a watery threshold lends it a mythic quality in Polynesian cosmology.

Fascinating Facts About Kure Atoll

- Kure Atoll is farther from a continental landmass than any other coral atoll on Earth, located over 3,600 kilometers (2,200 miles) from mainland Asia and North America.

- It features the oldest coral reef structures in the Hawaiian Archipelago—developed over 28 million years ago after volcanic rock began to erode and sink.

- Kure Atoll was once accidentally “claimed” by several groups, including American, Japanese, and Russian vessels, often without realizing it was part of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- The atoll lies near the edge of the North Pacific gyre, meaning large amounts of marine debris accumulate on its shores, including plastics from Asia and North America.

- Despite its remoteness, Kure Atoll has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International due to its support for over 18 nesting seabird species.

Access and Conservation

Visiting Kure Atoll is highly restricted due to its remote location and fragile ecosystem. Permits are only granted to researchers, conservation organizations, and occasional government missions that contribute to the protection and scientific understanding of the area. Access is typically made by boat from Midway Atoll, and expeditions can take several days through rough seas.

Conservation efforts focus on invasive species removal, habitat restoration, monitoring of migratory bird species, and reducing the impacts of marine debris. The atoll is protected under both state and federal law, and it plays a key part in the larger strategy of preserving the Pacific’s unique biodiversity and cultural legacy.

Conclusion

Kure Atoll stands as a remote sentinel at the edge of the Hawaiian Islands — a place where natural history, cultural legend, and modern conservation intersect. From its windswept sands to its vibrant coral reefs, Kure is a vital outpost for biodiversity, a spiritual waypoint in Polynesian heritage, and a stark reminder of the challenges facing isolated ecosystems in a rapidly changing world.