Boreray – The Remote Scottish Jewel of the St Kilda Archipelago

Boreray, sometimes affectionately referred to as “the island at the edge of the world,” is a remote and dramatic outcrop located deep within the North Atlantic Ocean off the western coast of Scotland. Part of the St Kilda archipelago, this uninhabited speck of land is simultaneously mysterious and breathtaking, defined by soaring cliffs, rich wildlife, and centuries of folklore.

Location and Geography

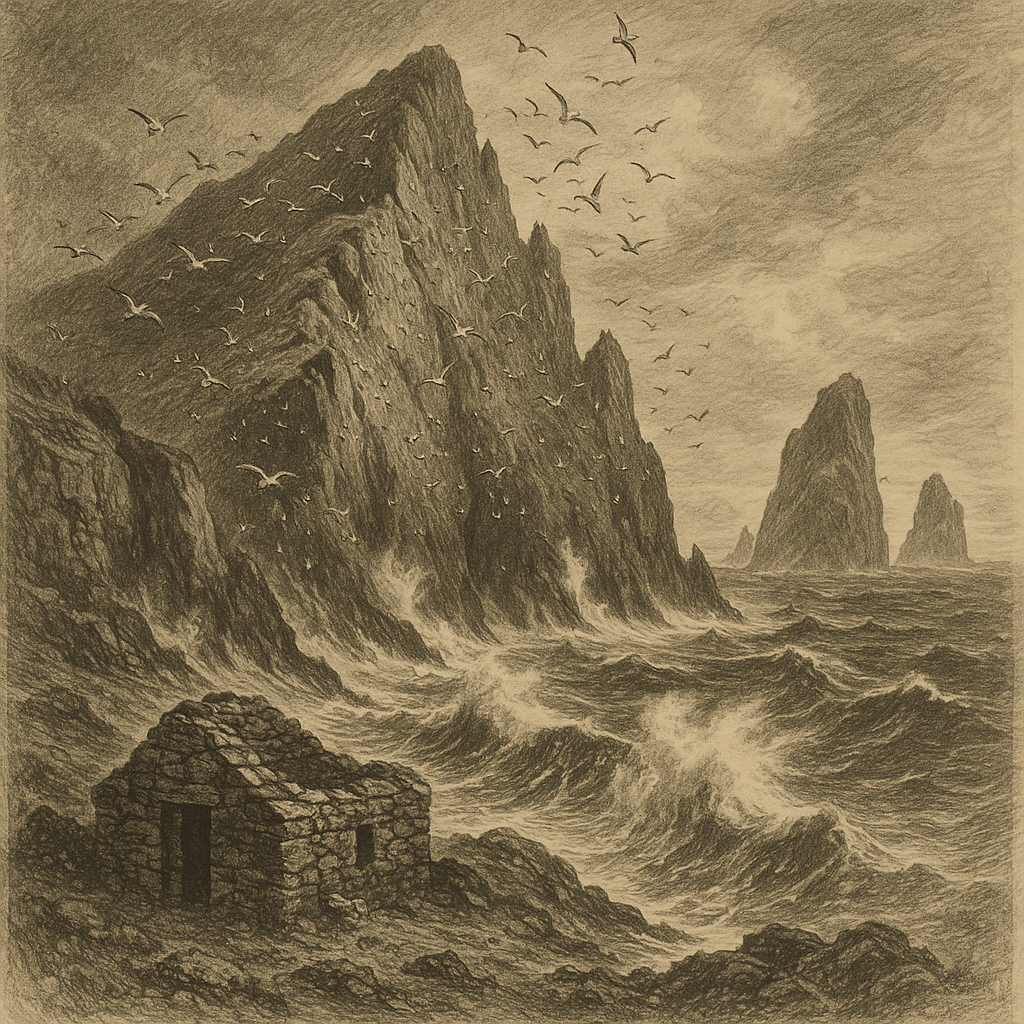

Boreray lies approximately 66 kilometers west-northwest of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland and is one of the most isolated points of the British Isles. Covering a modest area of about 86 hectares (0.86 square kilometers), the island is dwarfed by sheer cliffs that plunge vertically into the wild sea, with its highest peak, Mullach an Eilein, rising to 384 meters above sea level.

Belonging to the St Kilda island group — a UNESCO World Heritage Site — Boreray is surrounded by majestic sea stacks such as Stac Lee and Stac an Armin, remnants of ancient volcanic activity that have stood against the brutal force of the North Atlantic for millions of years.

Natural History and Wildlife

Despite its small size and harsh terrain, Boreray plays a crucial role in the ecology of the North Atlantic. It is one of the most important seabird habitats in Europe, designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a designated Special Protection Area. The island and its surrounding stacks are home to the world’s largest colony of northern gannets (Morus bassanus), with over 50,000 breeding pairs nesting across the cliffs of Boreray and its adjacent sea stacks.

Other seabird species include thousands of puffins, fulmars, kittiwakes, and storm petrels that find sanctuary in the steep ledges and crevices of the island. The surrounding waters teem with life — seals bask on rocky outcrops while whales and dolphins are occasional visitors, riding the cold currents that flow around the Hebrides.

Human Connection and History

Though it is uninhabited today, Boreray bears evidence of ancient human use. Archaeological remnants suggest that the St Kildans, the former residents of the main island Hirta, used Boreray seasonally for bird hunting and sheep grazing. Stone bothies (primitive shelters) built by these hardy people still dot the landscape of Boreray, though they have long been reclaimed by nature.

The island was inhabited only temporarily, mainly during the summer months, as part of the traditional transhumance practice in which young men would stay for weeks hunting seabirds and collecting eggs — often dangling perilously by ropes down the cliffs to reach nesting sites. The sheep of Boreray, a rare and ancient breed, are among the last remnants of human influence and still survive in semi-wild conditions.

Access and Preservation

Reaching Boreray is a challenging endeavor. The combination of volatile weather, treacherous seas, and the island’s sheer cliffs makes landings extremely difficult and rare. Access is typically only achieved by charter vessel from the Western Isles and requires ideal weather conditions and specialized skills.

Because of its ecological and cultural significance, Boreray is strictly protected. The National Trust for Scotland oversees the site as part of the St Kilda World Heritage Site, and access is restricted to preserve the delicate ecosystems. Scientific researchers and certain conservation programs are sometimes allowed monitored visits, but tourism is limited to offshore viewing from boats.

Curiosities about Boreray

Several aspects of Boreray set it apart from other islands in the British Isles. It is the only Scottish island apart from Hirta to be granted dual UNESCO World Heritage status — both for its unique natural environment and historic cultural landscape.

The sheep of Boreray, often referred to as Boreray sheep, are among the rarest breeds in the world. These sheep are a direct genetic link to ancient Hebridean stock and live almost untouched by modern breeding practices. They require no human management and survive purely through natural selection, making them one of the closest living examples of prehistoric domesticated sheep.

Incredibly, Boreray was never permanently inhabited, despite evidence of summer use. Its geography — all cliffs and no shelter — made it inhospitable for year-round habitation, yet vital in the seasonal rhythm of life for the St Kildans.

Legends and Folklore

Boreray, like much of St Kilda, is steeped in myth and legend. One of the most enduring stories passed down through generations involves a St Kildan boy who was punished by the spirits of the sea for taking more than what he needed from the island. According to local belief, Boreray was under the protection of ancient sea gods who ensured that only balance and respect were kept in human interactions with the island. Offending this balance would result in treacherous storms and shipwrecks.

Another legend speaks of the “cliff singers” — ghostly echoing calls heard at night that the St Kildans believed were the voices of ancestral spirits still tending to the flocks in the afterlife. These unearthly cries, often heard during the migratory passage of seabirds, gave the island an air of mysticism and sacredness.

There was even a belief that Boreray was guarded by a sea kelpie (a shape-shifting water spirit), which would misguide sailors who dared approach the island with greedy intent. These tales were not only part of the folklore, but also served as spiritual instructions to approach the island with reverence and humility.

The Enduring Mystery of Boreray

Boreray remains one of the most awe-inspiring locations in the North Atlantic — a silent sentinel that stands as a natural fortress against time, wind, and wave. Its refusal to yield to permanent human habitation, and its continued importance as a sanctuary for birdlife and a holder of ancestral memory, make it a truly unique place.

While inaccessible to most and unwelcoming to settlement, Boreray thrives in its majestic isolation. It is a symbol of the wild spirit of Scotland’s outermost isles — enduring, mysterious, and profoundly moving to those fortunate enough to catch a glimpse.