Introduction to Baker Island

Baker Island is a remote, uninhabited atoll located in the central Pacific Ocean, just north of the Equator. It is one of the most isolated territories administered by the United States and is part of the United States Minor Outlying Islands. This tiny speck of land in the vast Pacific has a fascinating history marked by guano mining, strategic military interest, and ecological significance. Due to its isolation and minimal human interference, Baker Island today serves as a protected wildlife refuge and offers a unique glimpse into nature’s resilience on a remote coral island.

Geographical Location and Physical Features

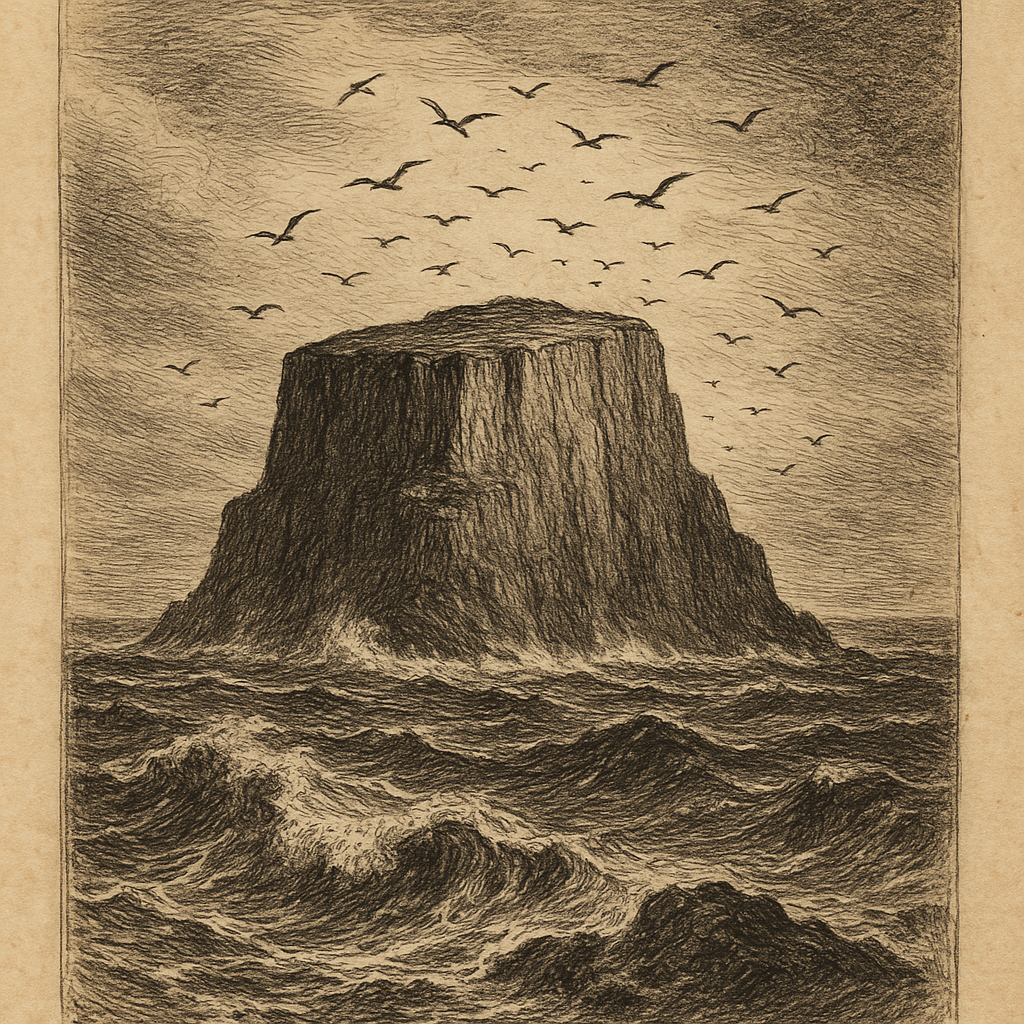

Baker Island is located approximately halfway between Hawaii and Australia, around 1,700 nautical miles southwest of Honolulu. It is situated just 13 kilometers north of the Equator and lies in the central Pacific Ocean. The island covers a land area of roughly 2.1 square kilometers (0.81 square miles) and is surrounded by a narrow fringing reef, beyond which the ocean drops off steeply.

The island is low and flat, with the highest point only about 8 meters (26 feet) above sea level. The landscape is arid and characterized by dry shrubland, grasses, and sparse vegetation due to the harsh, sunny climate and limited freshwater resources. There are no natural sources of fresh water, making long-term human habitation extremely difficult.

Geological Origin and Environment

Baker Island is a coral atoll that developed on an ancient volcanic seamount. Over millennia, the volcano subsided, and coral growth kept pace with the subsidence, eventually forming a flat, dry atoll perched above a submerged cone of volcanic rock. Its origin is thus similar to that of many other Pacific islands formed by hotspot volcanic activity followed by erosion and coral colonization.

The island’s environment is classified as tropical desert, with high temperatures and intense sun throughout the year. Rainfall is scarce and irregular, contributing to the island’s dry and barren appearance. The combination of its isolation and extreme conditions makes Baker Island a unique environment with specialized biodiversity.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecological Importance

Despite its hostile environment, Baker Island is home to a variety of seabirds, shorebirds, and marine wildlife. It has been designated the Baker Island National Wildlife Refuge since 1974, a status that protects its delicate ecosystem and places it under the administration of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Vegetation is limited but includes low shrubs, grasses, and small patches of herbaceous plants that have adapted to salty and dry conditions. The most striking biological presence on the island comes from its abundant bird life. Species such as the brown noddy, sooty tern, red-footed booby, and great frigatebird rely on the island as a critical nesting ground. The beaches are also used by nesting green turtles.

The surrounding reef ecosystem is rich in marine life, including a variety of corals, reef fish, and invertebrates, making the island’s waters an important area for scientific exploration and conservation.

Human History and Activity

Baker Island has a curious human history characterized by brief occupation and extensive abandonment. There is no evidence of long-term habitation by Pacific Islanders, although it is believed that Polynesians or Micronesians might have visited or known about the island in ancient times.

The first recorded sighting of the island was by Captain Michael Baker of a whaling ship in 1832, from whom the island draws its name. In the mid-19th century, it was claimed under the United States Guano Islands Act of 1856 due to extensive deposits of guano—a highly valued fertilizer at that time. Guano mining commenced and was carried out for several decades but ceased by the end of the 19th century when the deposits were depleted.

In the 1930s, the U.S. attempted to colonize Baker Island as part of the American Equatorial Islands Colonization Project, primarily for strategic and territorial reasons, as well as to establish a potential airfield for trans-Pacific flights. Civilian colonists, known as “American Equatorial Islanders,” were stationed there, but the settlement was abandoned at the start of World War II due to Japanese naval attacks.

Current Status and Access

Today, Baker Island is uninhabited and visits are restricted. The island is closed to the general public and can only be visited with a permit from the U.S. government, typically for scientific or educational purposes. There are no ports, harbors, or airstrips, and landings must be made by small boats through the fringing coral reef, making access extremely challenging.

The island is maintained as part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world. This designation helps to preserve the unique terrestrial and marine ecosystems and prohibit commercial exploitation.

Occasionally, the U.S. Coast Guard or researchers visit the island for monitoring and maintenance of navigational aids and ecological assessments.

Interesting Facts About Baker Island

– Baker Island does not observe any official local time zone and is often considered to be one of the last places on Earth where the date changes.

– The entire island is classified as a protected area, and its airspace and surrounding waters are also restricted.

– Due to its location almost directly on the Equator, Baker Island receives one of the highest average levels of solar radiation on Earth.

– Rusted equipment and remnants of old airstrip construction are still visible, a silent testament to its brief human occupation in the 1930s and early 1940s.

– The island has occasionally served as a stopover for trans-Pacific communication cables and oceanographic research vessels due to its strategic location.

Legends and Mysteries

Though largely devoid of a rich indigenous narrative due to the absence of native human populations, Baker Island has entered popular lore through its association with one of aviation’s greatest mysteries. One theory surrounding the disappearance of famed aviator Amelia Earhart suggests that her Lockheed Electra may have come down on or near one of the remote Pacific islands, including Baker or nearby Howland Island. While this theory remains speculative and no concrete evidence supports it, the narrative contributes to the mystique of these largely inaccessible atolls.

Additionally, the island’s remote and desolate setting has inspired tales among sailors and radio operators of ghostly transmissions and shipwrecked visitors, adding a layer of myth to its otherwise stark reality.

Conclusion

Baker Island stands as a testament to Earth’s remote and largely untouched natural world. Its isolation, unique history, and ecological value make it a point of interest for environmental scientists, historians, and even mystery enthusiasts. From its days as a guano mining site to its brief strategic military use and current role as a wildlife refuge, Baker Island has played diverse roles in human and natural history. Though inaccessible to most, its legacy as one of the last true frontiers of the Pacific endures.